How Google is Helping to Tackle Global Deforestation

07 November 2019

By H

The Amazon rainforest is really, really big. When I was growing up, we used to go for long walks in a forest called Newborough on the Isle of Anglesey, and it would take all afternoon to walk around it. I used to think that it was quite a big forest but, at its widest point, it’s a smidge over 3km wide. The Amazon is more like 3,500km wide and when Ed Stafford walked the length of the Amazon River, it took him 860 days. The sheer size of it presented the Brazilian government with a difficult challenge when trying to monitor Amazonian deforestation.

From as early as the 1970s, Brazil has based estimates of deforestation on satellite imagery. However, to do this accurately required a high level of detail as much of the destruction was being caused by a large volume of hard-to-detect, small-scale clearing or logging projects.

These images show an example of deforestation in a part of the Amazon Rainforest from 2000, to 2005 to 2010. Source: Deforestation of the Amazon

The computing power and storage needed to process these large image files was both time-consuming and expensive. Although conservationists needed to raise awareness of the growing problem of deforestation in Brazil and worldwide, these technological limitations meant that they were held back by inaccurate, incomplete and outdated data.

“In most places, we knew very little about what was happening to forests. By the time you published a report, the basic data on forest cover was years out of date”

– Nigel Sizer, the global director of the forests program at World Resources Institute.

Technological advance

The answer finally came years later at the 2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference and it came in the form of Google Earth Engine.

Google already knew a thing or two about cheap storage of data, powerful cloud computing and internet connectivity. Combine this with free access to years of NASA satellite imagery and the Google Earth Engine would enable scientists to analyse forest cover in fractions of a second.

This caught the attention of land-use expert Matt Hansen, who worked with Google Engineers to test this prototype on an ambitious project to map all of Mexico’s forests. It worked. At 30-metre resolution, the team created far more detailed forest maps than had ever existed before – a serious improvement on the current technology.

The next step was obvious, apparently. Map the entire globe. This would involve processing over 650,000 images – a task that would take a normal computer 15 years to complete. It took Google Earth Engine a few days.

“When we ran it, we dimmed the lights at Google”

– Matt Hansen

The Scale of the Problem

This was a scientific breakthrough and the results were unveiled in Science in 2013, but what they found was both alarming and distressing. The data gathered between 2000 and 2012 revealed that the world had lost the equivalent of 68,000 football fields of forest every day. That’s roughly 50 a minute. That’s one every 1.2 seconds. That little forest I used to walk through as a child is gone in something like half an hour. *sad face*

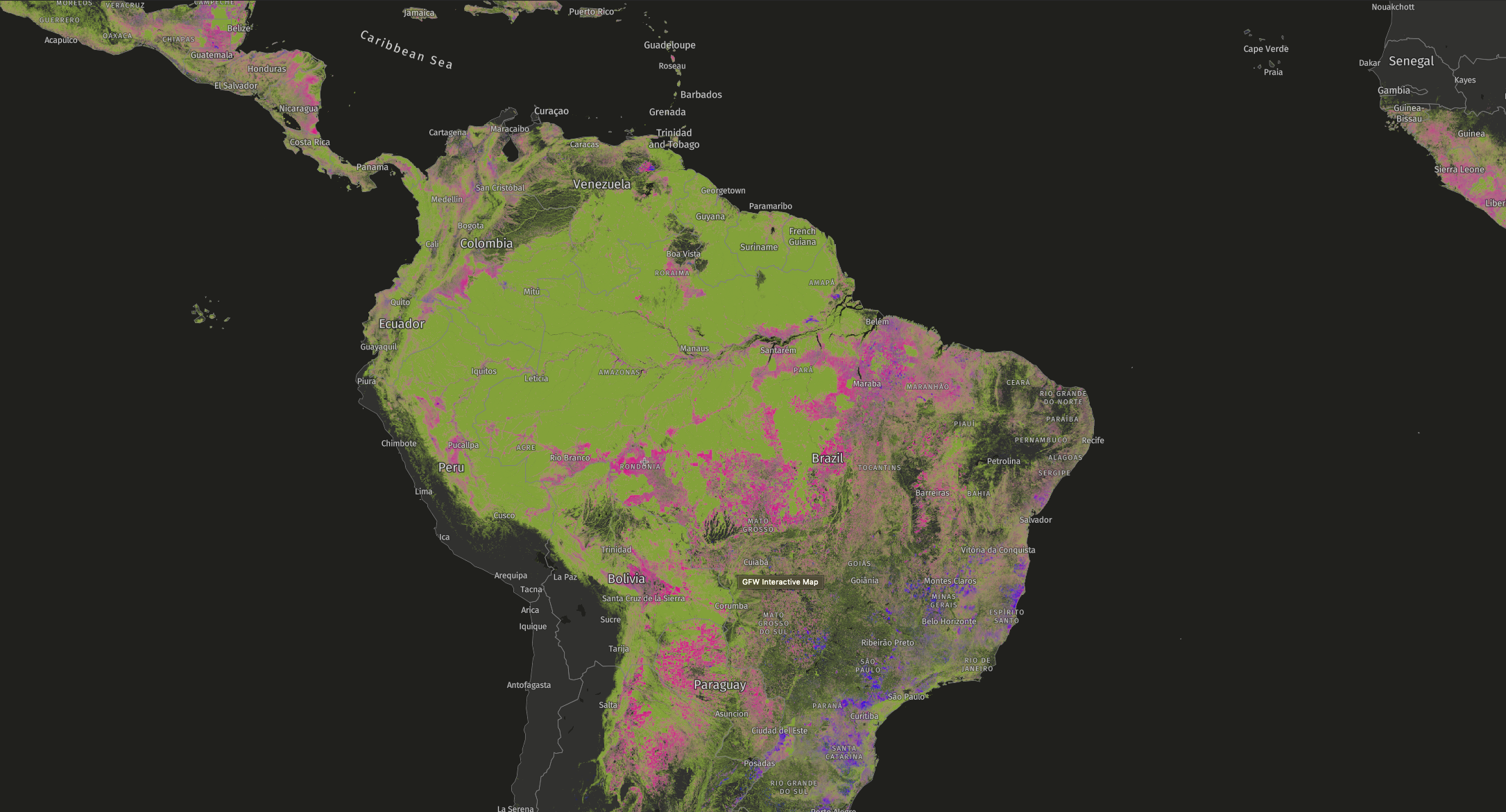

Global Forest Watch allows you to see forest cover loss and gain across the world since 2001.

The study also showed that this problem was not exclusive to the Amazon. Several “overlooked” countries had experienced a high percentage of forest cover loss, with Indonesia overtaking Brazil as the global leader in deforestation in 2012. In fact, the data showed that Brazil’s efforts to reduce deforestation were working.

Unfortunately, these efforts were offset by dramatic forest loss outside of the headline-making regions of the Amazon, the Congo and Indonesia. This study made it transparent that deforestation is a global issue driven by increasing demand for things like soy, beef and palm oil.

Although the results were dire and shocking, they also served as an important warning. This new research represented a positive step towards being able to better understand and reduce deforestation and also provided evidence that effective policy and enforcement could work.

Global Forest Watch

In light of their discovery, the Google Earth Engine team partnered with Global Forest Watch to produce accurate and transparent accounts of the state of forests and land use. Powered by Google’s cloud computing and storage resources, one of GFW’s key assets is speed. It has frequent updates to its data; typically every few weeks but as much as daily for key hotspots.

Since the launch, the data has been used by governments and private businesses alike to support sustainability promises and legislation, with its users also layering on additional valuable information such as land ownership. The outlook for GFW is to increase the freshness and resolution of its data in order to provide instant alerts to those who want to protect forests.

Wider impact

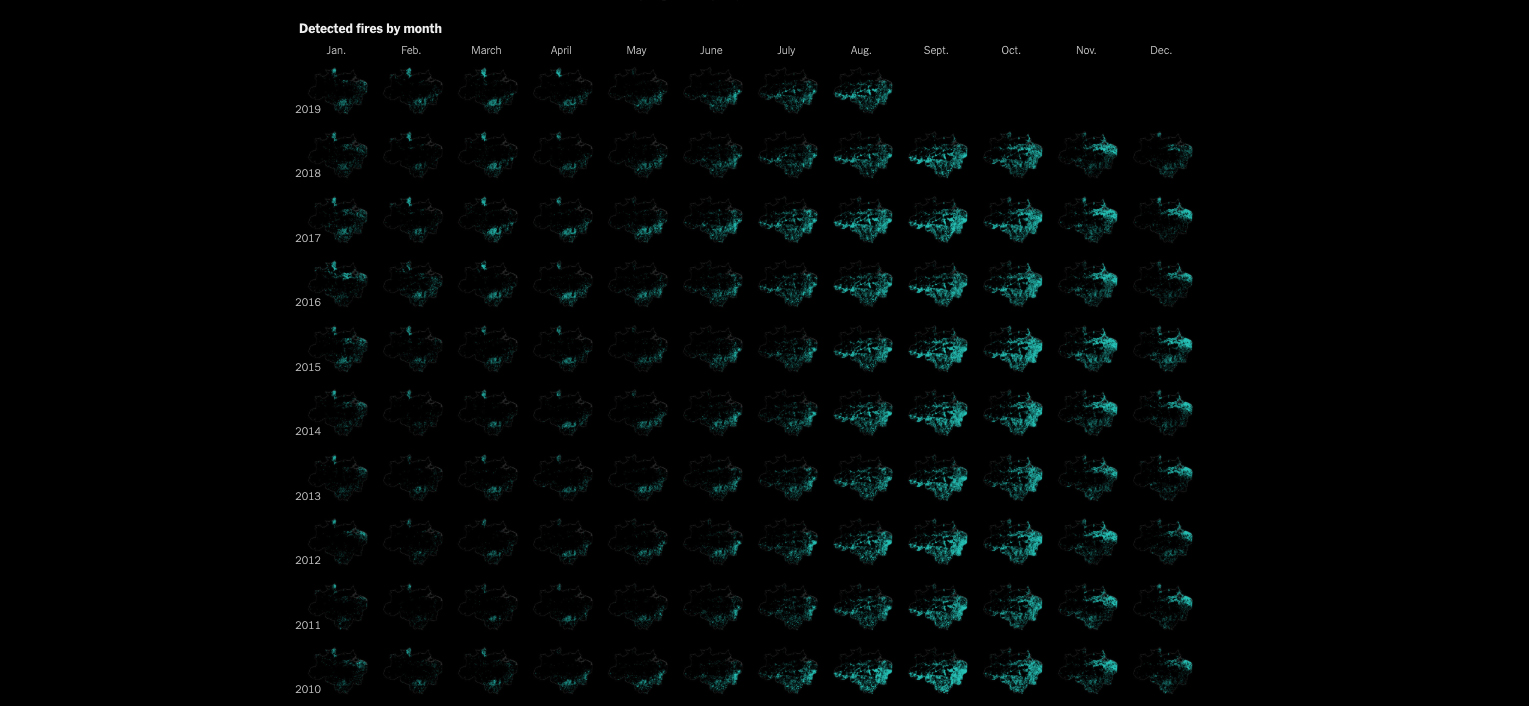

A greater understanding of deforestation has led to a greater understanding of some of its consequences and the wider impact on the environment. One topical example is the increase in forest fires, particularly in South America. The satellites used by GFW, NASA’s Terra and Aqua, can also detect the infrared radiation emitted by fires.

In the land created by deforestation for agricultural use, there has been a significant increase in fires – likely created by farmers preparing the land for next year’s planting. This is shown by the density of fires increasing in the months when farmers begin planting soybean and corn crops. Not only is this further damaging the ecosystem, but it is also endangering wildlife and destroying animals’ habitats.

This grid of maps from The New York Times shows the month-by-month pattern of fires across the Amazon rain forest in Brazil each year since 2001.

A satellite image published by NASA astronaut Ricky Arnold in 2018 showed an entirely different problem. The decimation of rainforests in Madagascar causes extreme erosion of the red-tinged soil in the Betsiboka Estuary. The few trees left are not enough to stabilise the barren earth and so soil flows into the waterways, creating a poignant image that one astronaut described as “Madagascar bleeding into the ocean”.

This satellite image shows the red soil of the Betsiboka Estuary are flowing into the ocean. Source: NASA

Looking to the future

There is a positive message to be heard here, however. The point I’m trying to make with this article isn’t that this combination of scientific endeavour, technological advance and big tech funding makes even more stark the real threats our planet faces from climate change and human-caused environmental destruction.

Although it does do that, these things also help us to shape and implement solutions to these issues. The computing power and resources that Google has applied to tackling deforestation has given us a greater understanding of its urgency. This means we can now take educated action against deforestation using extremely accurate mapping data – something that was inconceivable when Google was founded 21 years ago.

And this technology needn’t be limited to deforestation. Already, NGOs are using satellite imagery and predictive analytics to combat the unprecedented slaughter of elephants for Ivory in Garamba National Park in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

I would urge you to spend some time browsing Global Forest Watch’s map, where you see forest cover loss and gain anywhere in the world since 2001. Most of the data is alarming but you should also know that it is being put to good use. And yes, I do log on every now and then to check that little forest I used to walk around is still there.

HCW.